Too many management teams suffer through hours of wasted time and energy working step-by-step through sterile, inflexible, and often poorly designed planning processes. They have experienced the frustration of building a plan only to see it immediately laid aside the following day as the organization pursues business as usual. Over time, it is seen about as exciting as preparing the annual operating budget. It shouldn’t be a surprise that after many such planning experiences, these executives become cynical about the whole idea of planning and are hesitant to invest their time, energy, and emotional involvement in any planning endeavor. They come to the meetings as expected, but not really engaged. As a result, plans become even more anemic and irrelevant and the cycle reinforces itself.

The reality is that planning should be one of the most invigorating, motivating, fun activities in the work life of an executive. It ought to be so stimulating that they can’t wait for the next meeting. When done right, not only is the planning process itself dynamic and motivational, the effects are seen and felt on an organizational level strategic ambitions crafted by the collective IQ in the planning room become the operating reality in the market place.

This article highlights a few important planning principles and pitfalls that can turn hum-drum planning sessions into vision-busting thinking sessions needed to transform organizational realities.

So, “What is Strategic Planning?”

Planning is, in a nutshell, a set of intentional decisions predetermining a course of action. Strategic planning aims at a destination and, therefore direction of an organization. Any planning exercise that addresses either of these two issues is, by definition, strategic.

”Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.“

Sun Tzŭ, 490 BC

Chinese Military Strategist

The word strategy comes from the Greek word stratēgos, which means general. It’s a compound word: stratia (army) + agein (to lead). Strategy in this sense is the positioning of one’s troops for maximum advantage before battle. Tactics comes from the Greek word taktikos and refers to the maneuvering of troops during battle. Whereas strategy takes a long view of the forthcoming battle, tactics are focused on the more immediate issues during battle. Strategy is about positioning; tactics are about execution.

Although we can define strategic planning as a process (See Triaxia’s Strategic Thinking Cycle), it is not always a matter of working through the process from beginning to end. For many organizations elements of their strategic framework (e.g., vision, mission, values, goals, customer value proposition, etc.) are in place and working well. Often planning aims is to address one or more critical issues confronting the organization such as threats or opportunities that may hinder or help them realize their strategic aspirations.

Planning Principles

Painting the Golden Gate Bridge

Painting the 1.7 mile Golden Gate Bridge is an on-going task. When the 38 person painting maintenance crew gets to one end of the bridge, they go back to the other and start all over again. Organizational planning is like that. Whereas the Golden Gate must be continually be maintained to protect it from the corrosive effects of salt and wind, so too must organizations as they face the constant change that erodes the effectiveness of their strategies. Highly effective leadership teams are always planning – they see the process as one of their primary on-going responsibilities rather than a periodic event that should be accomplished every few years. They sometimes work through their planning model quickly using it as a checklist of important organizational themes to review and revise as needed or they select one or two pressing strategic questions that need to be wrestled to the ground. Regardless, planning is seen as a regular and continuing exercise in much the same vein as any other business discipline.

Adhering to certain key principles will facilitate the planning process itself and lead to a more robust and creative plan. Below we briefly review some of the more common and important planning principles:

“In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.“

– Dwight D. Eisenhower

“The majority of men meet with failure because of their lack of persistence in creating new plans to take the place of those which fail.”

– Napoleon Hill

“Have a bias toward action – let’s see something happen now. You can break that big plan into small steps and take the first step right away.”

– Indira Gandhi

“…chance favors only the prepared mind.”

– Louis Pasteur

“Life is the sum of all your choices.”

– Albert Camus

“You must stick to your conviction, but be ready to abandon your assumptions.”

– Denis Waitley

“We always plan too much and always think too little.“

– Joseph Schumper

Speaking about thinking, the collective IQ of the group is invariably brighter than the smartest individual in the group. A thoughtful, diverse planning team can surround discussion, deliberation, and decisions with multiple perspectives, experiences, paradigms, and skills. This dynamic leads to both richer sets of alternatives and higher quality decision-making. This principle would tell us to think carefully about the composition of the planning team and work diligently to insure that it had the brightest collective IQ we could assemble.

Planning Pitfalls

As there are principles that support your planning process, pitfalls exist as well. Common pitfalls might include the following:

- Confusing planning with forecasting and budgeting – For many organizations the budget is the plan. For a few others it’s the first step in the planning process and then the plan becomes how to get things done within the budget. In any robust strategic planning process, the budget is a step very near the end of the process.

Weak or unrealistic assumptions – Too often plans are based on guesses, gut feelings, and/or anecdotal evidence versus facts. Great plans are based on solid data. They confront reality and call things the way they really are. Just as importantly effective planners exercise the discipline to actually go out and find out how things really are rather than placing their faith in gut feelings. - Inappropriate planning and decision making process – Some of our best planning process ideas have come from books and examples from companies well-known for their planning and business prowess. However, to apply these ideas and approaches wholesale without commonsense adaptation to the specific needs of your organization is planning suicide. The process might sound sophisticated and somewhat avant-garde when you share it on the golf course but it is often an operational catastrophe in practice.

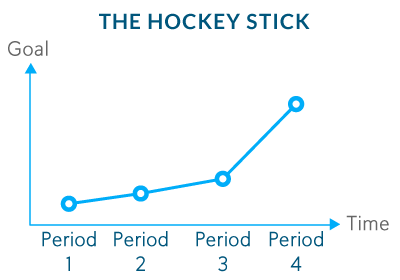

The Hockey Stick Unrealistic goals – Betting everything on the last year of a five year plan is one common illustration of an unrealistic goal. It’s so common that it has its own nick name, “The Hockey Stick” goal. It’s not uncommon for a team to have goals that are unrealistically high throughout the plan because of leadership expectations or corporate culture that demands super stretch goals as annual rite of passage. Goals come in an assortment of sizes: acceptable, exceptional, extraordinary, all the way to downright unbelievable. Forcing a planning team to accept unachievable goals year-after-year will, in fairly short order motivate some unhealthy executive behavior and poor corporate performance.

The Hockey Stick Unrealistic goals – Betting everything on the last year of a five year plan is one common illustration of an unrealistic goal. It’s so common that it has its own nick name, “The Hockey Stick” goal. It’s not uncommon for a team to have goals that are unrealistically high throughout the plan because of leadership expectations or corporate culture that demands super stretch goals as annual rite of passage. Goals come in an assortment of sizes: acceptable, exceptional, extraordinary, all the way to downright unbelievable. Forcing a planning team to accept unachievable goals year-after-year will, in fairly short order motivate some unhealthy executive behavior and poor corporate performance.- Weak, ineffective strategy – A common pitfall is to put all of the planning energy into goal setting and pay lip-service to the underlying strategy and tactics that will make those goals a reality. Goals don’t just happen, no matter how desirable they might be.

- Lack of leadership and staff skill sets needed for implementation – There are plenty of case studies in which companies developed plans and goals that exceeded their leadership bench strength and skill sets. A wonderfully creative plan is useless unless it can be implemented.

- Lack of contingency plans – If there is a truth to be found in planning, it is that plans never go as planned. Not long into the journey toward new goals the company will run into the inevitable potholes, roadblocks, and detours. The originally determined plan seldom equals the resulting emergent plan that gets devised along the way. Wise leadership teams embed this insight into their planning process and consider what they might do if things don’t go as planned before they even start the journey.

- Lack of commitment of people to the goals and the strategy to achieve them – Who needs to do what to make this team a reality? How would they know that? What would motivate them to invest the energy to achieve these goals? These and other key questions must be answered in the planning process, but are often overlooked or ignored as being secondary to having a really good plan. A really good plan is one that achieves its intended results. For a strategic plan, that involves virtually everyone in the organization. Great answers to these and other similar questions are as important as robust goals and creative strategies in the strategic planning process.

One Last Point

Principles and pitfalls are two sides of the same coin. A principle applied is a pitfall avoided. Let us close with a very important principle/pitfall. As to the principle, many companies find great value in leveraging outside expertise in their planning initiative. Some more common benefits might include objective perspectives, process expertise, the ability and willingness to make sure the leadership team asks the hard questions, and courage to challenge soft answers to those hard questions.

The pitfall is to allow the consultant to have too much influence over both the planning process and the outcome. Your plan needs to be your plan, not the consultant’s. The process needs to reflect the specific needs, culture, skills, and ways of doing things in your organization, not a boilerplate process out of the latest bestselling management book. Basically, the consultant needs to see his or her role not as something he or she does to or for you but rather with you. The line between not enough facilitation and too much is very thin but also very important.

The above insights are not “plan-changing” in themselves but together, they can breathe new life and effectiveness into your planning process. We have seen a number of organizational leaders share these points and then ask the planning team to add to the list from their experience. It has proven to be an excellent way to launch the planning endeavor and to head off the influence of previous bad planning experiences residing in the heads of many of those sitting around the table.