Truly great organizations are crystal clear about where they are going, why they are going there, how they will make the journey, and the rules of the road. The idea of a journey is a good metaphor for the grand task of establishing the destination (and, by definition, direction) and mapping the strategy needed to get there.

The elements of strategic planning fall into two broad categories:

From here, planning gives way to execution – implementing the plan, monitoring progress, and making mid-course corrections as opportunities and/or threats reveal themselves along the way.

The focus of this article is on setting direction because if we don’t get this right, no strategy, no matter how brilliant, creative, and well-executed will bring us success. Three key elements define the destination and broad direction of an organization:

Before digging into the details of each of these ideas let us suggest a caveat. The objective is to create a description of organizational direction that is crystal clear to all stakeholders. Only to the extent that these specific elements contribute to this objective are they of any value. All of us have been exposed to mission statements that seemed to have no earthly connection to what was really going on in an organization – statements written with liberal doses of jargon, reflecting the business fads of the moment, and stated in such general terms that it might apply equally well for any organization no matter what they did. When all was said and done, the result was well-packaged nonsense that was of little use to anyone and quickly relegated to the ubiquitous three ring notebooks on the lower shelves of our office bookcase. Its only benefit was to allow us to respond with the “correct” answer to the question of the next planning consultant when asked, “Do you have a mission statement?”

On the other hand, many companies that really do have directional clarity don’t always have all three of these elements in place. Some make do with one of two. Others, often young, founder-led organizations, have a culture that is so connected where they are going and why they are going there that these ideas are firmly embedded in everyone’s heads and heart and no documents are needed for reference.

Unless these three ideas are sincere, authentic, and truly anchored in the DNA of the organization, they will serve no useful purpose.

Mission – Why We Exist

Mission explains why an organization exists, its fundamental calling and raison d’entre. It explains the underlying motivation for creating the organization to begin with. It defines the “domain” or boundaries of organizational commitment and effort. Activities, strategies, and outcomes that fall within those boundaries are acceptable (assuming they meet the requisite value commitments and achieve their intended goals); those that are outside those boundaries are unacceptable.

The mission statement is both a communication tool and decision framework. From a communication perspective it is an important vehicle to ensure that the organizational stakeholders (in particular the organizational staff) have a common view of what value the organization is attempting to create, for whom, and by what means.

The value of a well-crafted mission-statement is often unappreciated by an organization’s executives because they never understood the in addition to communication, the mission statement is a powerful decision tool.

Every organization exists to create value for the constituents it serves and a mission statement is the primary tool used by both the board of directors and organizational management to determine what activities the organization will do (and, by definition, not do) to create that value. As such, a mission statement speaks to the head for decision helping the board and management team make tough choices among good alternatives as they design organizational strategy. An effective mission identifies the constituents (“customers”) the organization serves, the products or services it provides those constituents, and the benefits or results (i.e., value) constituents receive from these products or services. Often the basic strategy or critical activities used to create and distribute the services are also included. These mission elements create boundaries for what the organization does and does not do to create value for its constituents.

A good mission statement is essentially about making choices. Almost without exception the development or, at a minimum, the approval of the mission statement is the purview of the board of directors. In drafting, reviewing, or revising a mission statement, it’s helpful for the board to discuss what boundaries are important to define. Examples might include:

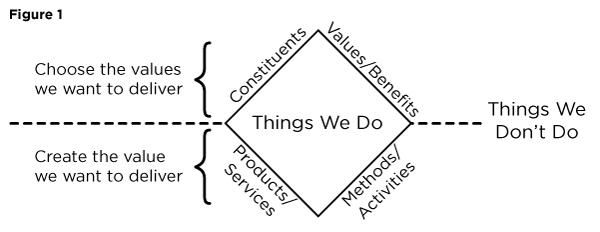

No mission statement would address all of these issues but most would include the hard choice of determining who the organization’s customer is (who we will and will not serve), the product/service it will provide (what we will and will not do), and the benefits (value) the organization will provide these targeted customers. Figure 1 illustrates the frame or boundaries that a mission provides. In this illustration the drafters included constituents (customer), products/services, the value provided, and core strategies. Anything within the frame is what we should be doing, anything outside the frame is, by definition, “out of bounds” for the organization.

No mission statement would address all of these issues but most would include the hard choice of determining who the organization’s customer is (who we will and will not serve), the product/service it will provide (what we will and will not do), and the benefits (value) the organization will provide these targeted customers. Figure 1 illustrates the frame or boundaries that a mission provides. In this illustration the drafters included constituents (customer), products/services, the value provided, and core strategies. Anything within the frame is what we should be doing, anything outside the frame is, by definition, “out of bounds” for the organization.

One important role of a mission statement is that of a decision framework that helps the board and management of the organization decides what to do and not do. Over the past few years, Triaxia Partners has facilitated the strategic plans for hundreds of organizations. Recently, we reviewed what we found to be the most typical problems these organizations faced in the strategies and overall organizational effectiveness. The number one culprit was a murky mission—mission statements that were so broad, vague, and jargon heavy that they were of no use in making program or strategy decisions.

Without diluting the conviction we have about the above observation, we must also introduce the observation that often the most successful organizations are “opportunistic” when it comes to finding worthwhile but unplanned goals, new customer segments and needs to serve, and new strategies. However, there is a fine line between opportunism and focus. Invariably the really successful organizations have a well-defined mission statement and planning framework that allows them to effectively sift good opportunities from disguised distractions. They also have the organizational discipline and managerial courage to abandon old ideas that that have lost their productivity as they add newer more potent one that will better achieve their strategic aspirations. Many less effective organizations add the newer ideas, (products, services, strategies, programs, etc.) while, at the same time, continuing to drag the old ones along behind them. One frustrated corporate executive observed it was like having to pull a refrigerator through the sand behind them as they attempted to move forward.

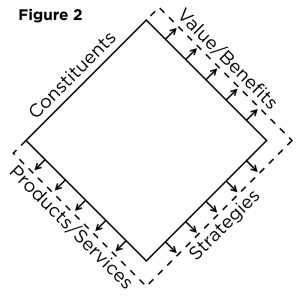

In Figure 2 we see the possibilities of adding a product or service, developing a new core strategy, or redefining the value the organization wants to provide its customers. By making these decisions within the context of mission (Why are we in existence?), such changes are deliberate and well thought through. Note that the diagram could also be drawn to show the arrows pointing the opposite direction. That is, dropping a particular product or service or to stop serving a certain type of customer.

Mission is the broad aim toward which we move. Jim Collins reminds us that it is like a “guiding star on the horizon”, forever pursued and never reached.2 We would disagree with Collin’s observation that the mission statement (core purpose) of an organization never changes. In reality it should, but not much and not often. The mission must remain congruent with the context (market realities) in which it is pursued. Customers change, new technologies are introduced, legislation is introduced — be it a giant change that suddenly changes the rules of the game or a constant series of small changes that, over time do the same thing, at some point organizations must deal with it if they are to remain relevant to those they serve.

Even without the push of emerging external forces, innovation within the organization itself may bring about needed change. For example, Kodak leaving film behind and pursing digital cameras and photography as technology trends made their old product line obsolete. In today’s world, Kodak’s mission is about images, not film. The mission statement needed to be adjusted to account for a new version of the original service, a much different strategy, and enhanced benefits that were being delivered to their customers (Figure 2).

Seen in this light, it should be clear that a major change in strategy (e.g., new customer categories, adding or discarding products or services, changing the value proposition offered to customers, etc.) should quickly send us back to our mission statement for either confirmation that we have remained with it its bounds or, if not, a reflective conversation about either forgoing our new strategy or changing the mission statement so the two are in alignment.

As to length, the debate continues some pundits believing a mission statement should be short; the rest convinced it should be very short. According to popular folk legend, Abraham Lincoln was once asked by a reporter, “How long should a man’s legs be?” Lincoln as said responded, “Long enough to reach the ground.” That same philosophy applies to a mission statement. The mission statement needs to be long enough to clearly communicate the raison d’entre for the organization to the targeted audience. No more, no less.

As to the criteria for good mission statements, that too is in much debate. Even though mission statements are not necessarily designed for inspiration, they need to provide as much organizational energy as possible. We often use the following criteria to evaluate mission statements:

Clear: Is this mission statement straightforward and understandable? Is it brief and easy to remember?

Relevant: It clearly describes what we truly want to achieve and/or become. Therefore it is seriously important to us

Significant: Here we refer to the scope or amount of what will be accomplished if we are successful in our mission – To motivate exceptional levels of effort the reward must be both relevant and significant

Focused: Does it clearly identify whom we will serve, what we are trying to accomplish and what our primary strategies (e.g., price, service, speed, innovations, etc.) might be. Can the board and management clearly discern which strategies and products “fit” and which don’t by using the mission statement as a decision framework?

Believable: Mission statements filled with aspirations that are clearly out of reach or even contrary to what the organization actually believes or does will be looked at with disbelief even distain and eventually discarded by those for which it was written. Embedded phrases like “to be the best…”, “to be number one”, are risky for organizations that are well back in the pack and have not demonstrated a commitment or capacity for growth and advancement. However, if such an effort is underway and there is some evidence of progress, such a bold statement may not only be believable but motivational and that brings us to the next criterion.

Inspirational: Inspires dedication and alignment in the entire organization. Relevant, significant, and believable lead up to inspirational– people really do invest more energy and effort into work when they believe it is connected to goals they really care about.

Different: Great organizations have some dimension that sets them apart from others – they are differentiated in some major respect. One test might be to ask the question, “Is it clear what would go away (if anything) if our organization went out of existence?”

Vision – A Picture of Mission Being Fulfilled

Vision describes what the organization aspires to be – what the organization desires its future to look like if they are successful with their mission and thus it speaks to the heart for inspiration generating the levels of passion and courage within the organization to energetically pursue this mission.

A vision statement is the other side to the coin of a mission statement. It is a picture of a mission fulfilled. Where as, mission speaks to the head for decision, vision speaks to the heart for inspiration. “Can you imagine if…”

Generally, vision statements are longer than mission statements, filled with descriptive adjectives, and often make liberal use of imagination. Whereas we would only hope that a mission statement might be inspirational, we must insist that the vision be so. They don’t have to be long but they must be powerfully vivid, painting pictures with words on the minds of those we want to enlist in the journey.

Kouzes and Posner (Leadership Challenge) define vision as an ideal and unique “image” of the future.3 Warren Bennis agrees, noting that a leader (or organization), in order to provide direction must first have developed a mental image of a possible and desirable future state of the organization.4

A vision is an articulated view of a realistic, credible, and attractive future for the organization. It is a mental picture of future accomplishment (of purpose fulfilled). Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone “visualized” a universal network of telephones as early as 1878. He wrote, “telephone wires could be laid underground, uniting private dwellings, counting houses, shops, and manufacturers with a central office, establishing direct communication between any two places…in the future, wires would unite offices of the telephone company in different cities, a man in one part of the country may communication by word of mouth with another in a different place.”

Bell saw the need to direct every activity to the accomplishment of this vision. “I am press upon you all the advisability of keeping this end in view, that all arrangements of the telephone may eventually be realized in the grand system.”5

Vision-Valley-Verity

Lee Eisenberg, exploring the concept of visionary leadership observed: “while their contemporaries groped at the present to fill a pulse were considered to past to discern the course that lead to the moment, visionary squint through the veil of the future. ”6 (Figure 3)

A few years ago there was Shearson/Lehman brothers’ advertisement that captured the though as well: “vision is having an acute sense of the possible. It is seeing what others don’t see and when those with similar vision are drawn together, something extraordinary occurs.7

Kouzes and Posner believed that vision statements have four criteria:8

- Future oriented: They are our destination. They are looking forward. Visions are statement of destinations, of the ends of our labors.

- Image: It is a “See” word. We hear managers talk about focus, foresight, big picture, etc.

- Ideal: Vision provides a sense of the possible. Visions are possibilities about desired futures. Note the difference between possibility and probability. Probabilities need evidence strong enough to establish the presumption, possibilities do not. Pioneering leaders assume most anything is possible.

- Unique: It’s our vision sets us apart from anyone else. Podestrq Baldocci, a florist, wrote, “we don’t sell flowers, we sale beauty.”

Vision gives focus to human energy. It provides the passion and perseverance to keep going when the inevitable obstacles between us and our vision arise. Wise leaders know there is a valley between now and the future they pursue. Vision is the fuel for the fight as followers plod through these valleys that challenge the end result they all desire. It is important to remember that vision is not a 20/20 picture of the future but rather, a statement of organizational ambition.9 They are paradoxical in that, on one hand they can seem highly specific and, on the other, vague and ill formed.

Being two sides of the same coin, the lines between vision and mission are blurry—few agree on where one stops and the other begins. Even fewer can agree on the definitional difference between the two. If you take the time to read through Abraham’s book which displays over 300 corporate “missions”, you will find a large number of Fortune 500 companies which do not even have what they call a mission statement preferring to go only with what they call a vision statement which serves both purposes. We believe that distinctives and very different roles of the two ideas make it worth the effort to create/discover mission and vision individually.

Values – The Rules of the Road

Values are what the organization stands for, the guiding principles that influence both “who and what fits around here.” Basically, values are an organization’s standards of behavior. The most powerful values go beyond the generic plaques on the wall, and prove to be a reliable guide to decision making and staff behavior.

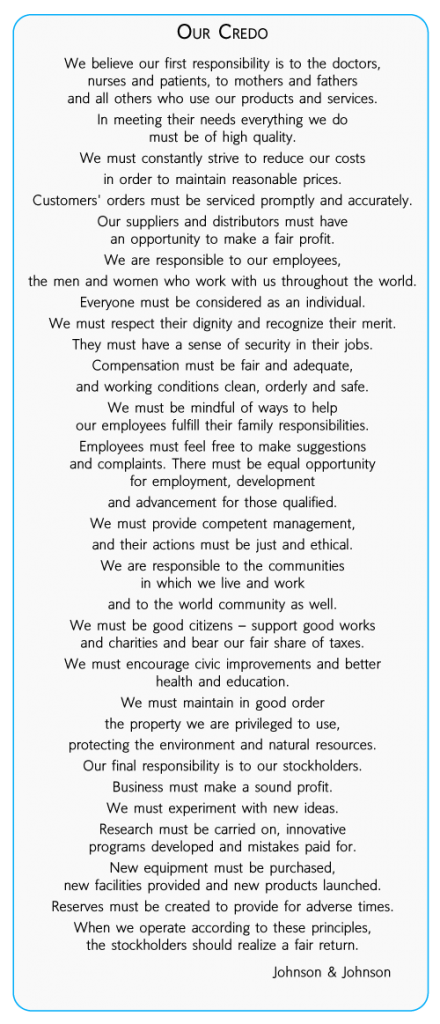

Highly effective organizations have well defined values and live by them sometimes at great cost. McNeil Consumer Products was given an opportunity to test the strength of its values in the early 1980s. In the fall of 1982, McNeil Consumer Products, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, was confronted with a crisis that could appear to spell the demise of its most profitable brand. Seven people living in the same area of Chicago died after unknowingly taking Extra-Strength Tylenol capsules laced with cyanide. Nationwide panic quickly spread with the news.

It was soon clear that the tampering came after manufacturing and distribution. The tainted bottles came from different manufacturing lots. It was determined that someone collected boxes of the product from several stores, inserted the poisoned capsules and then clandestinely replaced the products in various local drug stores. Johnson & Johnson needed to find the best way to deal with the tampering, without destroying the reputation of their company and their most profitable product, Tylenol.

In responding to the crises, Johnson & Johnson’s board and top management turned immediately to the J&J Credo, a one page document of principles (values) used since 1943 to guide the company’s responsibility to customers, stockholders, employees, and the community. No one doubted that customer safety came first, well above concerns of profit and other financial considerations. The company immediately alerted consumers across the nation, via the media, not to consume any type of Tylenol product. They also immediately stopped production and advertising of Tylenol and recalled all Tylenol capsules from the market. The recall included approximately 31 million bottles of Tylenol, with a retail value of more than 100 million dollars. Informed observers thought the brand had little possibility of coming back. Many marketing experts thought that Tylenol was doomed by doubts that the public may have had to whether or not the product was safe. “I don’t think they can ever sell another product under that name,” advertising genius Jerry Della Femina told the New York Times in the first days following the crisis.”10

Della Femina did not prove to be a prophet. J&J’s customers and the American public at large responded to the company’s forthrightness, fast action, and putting consumer safety above all financial considerations with strong support of the brand as, over time it was returned to retail shelves. By the end of 1982, Tylenol had nearly regained the leading market share that it enjoyed before the incident.

There are similar cases in which companies had put themselves first, and ended up doing more damage to their reputations than if they had immediately taken responsibility for the crisis. An example of this was the crisis that hit Source Perrier when traces of benzene were found in their bottled water. Instead of holding themselves accountable for the incident, Source Perrier claimed that the contamination resulted from an isolated incident. They then recalled only a limited number of Perrier bottles in North America.

When benzene was found in Perrier bottled water in Europe, an embarrassed Source Perrier had to announce a worldwide recall of the bottled water. Apparently, consumers around the world had been drinking contaminated water for months. Source Perrier was harshly attacked by the media. They were criticized for having little integrity and for disregarding public safety.11 In some respects these two very real case studies demonstrate that companies will either live by their values or die by them.

To be truly effective, the defining and deploying an organization’s values must adhere to several important principles.

Principle One – Discovery versus Design

Describing values is more a matter of discovery of deep-seated principles the organization is already applying, rather than defining and imposing a new set of standards. Every organization has values that they live by – values, even though tacit and unexamined really do influence behavior and decisions among the managers and employees. Collins and Porras in, Built to Last, observe that “visionary companies don’t ask, what shall we value? They ask what do we actually value deep down to our toes?”12 The origins of some of these values might be found embedded from the time when the organization was first started. It is these values that must be identified and then made more visible in the scheme of things and “how we do things around here.”

In the process of discovery a really bad idea is to use the lists of values from the latest best selling business book or other organizations, no matter how inspiring those values are nor successful their possessor. To be authentic your values must emanate from your organizational gut. Upon close examination, you might find they are very much a part of your corporate DNA.

Principle Two – Authenticity versus Appearance

The Enron Corporation proudly displayed its core values in its 2000 annual report:

Communication – We have an obligation to communicate. Here we take the time to talk to one another…to listen. We believe that information is meant to move and that information moves people.

Respect – We treat others as we would like to be treated ourselves. We do not tolerate abusive or disrespectful behavior.

Integrity – We work with customers and prospects openly, honestly, and sincerely. When we say we will do something, we will do it; when we say we cannot or will not do something, then we won’t do it.

Excellence – We are satisfied with nothing less than the very best in everything we do. We will continue to raise the bar for everyone. The great fun here will be for us to discover just how good we can really be.

By February, 2001, Andersen partners in Chicago were actively debating whether to retain Enron as a client as they became increasingly concerned with the company’s aggressive accounting decisions. Although concern was growing, they elected to stay with the client. By December 2001 Enron was in a state of melt down. Post collapse autopsies have found that virtually every corporate value which Enron espoused was ignored if not consciously violated. You know the rest of the story.

Principle Three – Clarity versus Confusion

Many organizations work diligently to ensure their list of values are stated in the most eloquent terms. Their intentions are good. They assume that the more creative the language, the more inspirational and memorable the list will be to the employees. The risk is that these attempts at creative prose might come across as either insincere or just downright ambiguous and confusing.

One Australian company selected the following as one of eight core values: “We believe that we have a responsibility to each other to ensure, through constructive confrontation, that we are all working to the highest level of our capability. We fight for excellence.“13

I suspect that we can work our way through the meaning of this in very general terms but it does leave things open to one’s interpretation. Are we always to use constructive confrontation to let a co-worker know if they are not pulling their load? How would one define what is constructive confrontation and what might be more negative, even destructive in its effect? What does “we fight for excellence” mean? Work hard to achieve it or, looking at the previous sentence in the value, be willing to fight with one another to propel one to higher levels of accomplishment?

Earlier we observed that the objective is to create a description of organizational direction that is crystal clear to all stakeholders. Only to the extent that these specific elements contribute to this objective are they of any value. In this example, we suspect the work in writing the statement greatly exceeded its benefits.

Principle Four – Enduring versus Ephemeral

Arthur Wyatt, a professor of accounting at the University of Illinois and formerly a managing director at Arthur Anderson & Co., provided an excellent chronicle of the demise of the reputation of American audit firms in general and Anderson in particular at the annual meeting of the American Accounting Association in 2003. Wyatt noted that the decline was not precipitous but rather happened slowly over a 30 year period of time.14 His explanation reminds us of the proverbial cooking of the frog.

Beginning in the 1960s services other than audit (primarily consulting) were beginning to make their way onto the menu of client services offered by the larger accounting firms. Over time, the higher margins and rapid growth of these consulting services gave those who led the efforts within the firms a greater voice in firm management and put increasing pressure on the audit side of the house to grow revenues and increase margins. Improved profitability became a major influence in the thinking of firm leadership often oppressing the traditional voice calling for professionalism and tough minded application of accepted accounting standards. The growth and profits experienced by the accounting firm clients in the go-go business environment of the 90’s did nothing to ameliorate a growing desire to have a piece of the economic pie being enjoyed by business at large. Wyatt observes, “In retrospect, it is easy to see the greed factor at work. At that time, however, the changing focus on revenue and profit growth was viewed merely as adapting to the changing times.”15 Expedient thinking overwhelmed ethical considerations. Pragmatism pushed aside idealism and ideology. Wyatt notes that “the core values of the firm were undermined by primarily commercial interests.”

Following this path has significant consequences for those who abide by it. Accommodation invariably leads to assimilation. In Arthur Andersen’s case they evolved slowly, over time (Like the Frog in the Kettle) from a standard bearer of good accounting standards that would protect investors and creditors to co-conspirators. Again, Wyatt weighs in: “Clients were able to more easily persuade engagement partners that their way of viewing a transaction was not only acceptable but desirable….Healthy skepticism was replaced by concurrence…The gradual changes in internal firm culture effectively altered the long-standing value systems of firm leaders.”

The inevitable happened. In 2002 the firm voluntarily surrendered its licenses to practice as Certified Public Accountants in the U.S. pending the result of prosecution by the Department of Justice over the firm’s handling of the auditing of Enron.

Values transcend the transient and short-lived business cycles and fads. Their benefit is that they provide the magnetic north that helps individuals and firms of individuals navigate the turbulence of change and confusion. They are, in every respect, the ethics of an organization. Ethics are personal and are felt down to the bone. There are many instances in which individuals and even organizations are willing to die rather than compromise them. Look again at the possibilities confronting the management and board of directors at Johnson& Johnson as they pulled Tylenol off the shelf in early 1982.

In closing, we want to reinforce the big idea. It’s not a set of documents that is the issue here but rather directional clarity for the organization. However that is achieved it is acceptable. Too many organizations get caught up in the form of writing these statements to comply with the expectations of virtually every strategic planning exercise and miss the substance behind the effort. If the typical employee in your company knows where you want to go and why it’s important to go there, you have succeeded. Without such clarity your organization will become quickly lost, distracted from your purpose, or even capsized in the inevitable storms and turbulence that you will encounter along the way.

It is generally in such storms that leaders come to grips with the important role the idea about mission, vision, and values plays in providing direction and help in navigation. At this point, however, it is too late. These are not ideas developed in the midst of a storm. Rather they are the product of reflective thinking of where we want to go as an organization, why we want to go there, and the rules of the road that will govern the decision making and behavior along the way. They are best developed before the organization sets out on its journey.

One Last Thought

We suggest that these three components of direction portfolio be separate documents rather than a single composition. Integrating these ideas into a single document generally results in lengthy, complex, confusing “tome” that is of no use to anyone. Each of the elements plays a very distinct and different role in describing the overall direction of the organization. To combine them leads to a weakening of their separate roles and most often produces a clumsy, confusing, and ineffective document that is of little use for providing organizational direction, particularly to those whose hands are on the organizational tiller steering in changing seas that can challenge the course to our intended destination.16

Footnotes:

1 In this document we see mission and purpose as synonyms and use them interchangeably

2 Building Your Company’s Vision, James Collins and Jerry Porras, HBR, September-October, 1996, p. 65-77

3 The Leadership Challenge, James M. Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner, 1987, Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, p.85

4 Leaders, Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus, 1985, Harper & Row Publishers, NY, p.89

5 Letter by Bell to some English capitalists in 1878 – Quoted in The History of the Telephone, Herbert N. Casson, A.C. McClurg & Co., Chicago, 1910, p.29

6 The Leadership Challenge, James M. Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner, 1987, Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, p.84

7 Ibid

8 Ibid, pages 87-91

9 Shapiro, Fad Surfing in the Boardroom

10 Broom, Glen M., Allen H. Center, Scott M. Cutlip. Effective Public Relations, Seventh Edition. Prentice-Hall Inc. 1994. p 59, 381 as quoted in The Tylenol Crises by Tamara Kaplan, The Pennsylvania State University

11 Knight, Jerry. “Tylenol’s Maker Shows How to Respond to Crisis.” The Washington Post. October 11, 1982. as quoted in The Tylenol Crises by Tamara Kaplan, The Pennsylvania State University

12 James C. Collins and Jerry I. Porras, Built to Last, Harper Business Books, 1994, page 9

13 Eagle Datamation International (EDI), an Australian software provider – As shown on corporate web page

14 Accounting Professionalism – They Just Don’t Get It, A speech by Arthur Wyatt, AAA Annual Meting, Honolulu, Hawaii, August 4, 2003

15 Ibid

16 Many organizations (e.g., Honeywell, Kelly Services, Pillsbury, etc.) display all three ideas in a single document in their finished form, but the individual elements were developed individually before being consolidated into a single presentation